Louisiana case brought pedophilic priests into the open

By Carl M. Cannon

Mercury News Washington Bureau

San Jose Mercury News

December 31, 1987

[See a linked list of all the articles in the Priests

Who Molest series.]

Abbeville, La. — If ever there was a place in America where the

secret of a pedophilic priest would have remained inside the church family,

it was here on the bayou, where forgiveness of sin is part of the political

culture and judges, police officers, civil lawyers — 80 percent

of the population, in fact — are Roman Catholics.

But even the deeply devout Cajun community could forgive only so much.

At 7:00 a.m. on June 23, 1983, a strapping farmer, trapper, and seafood processor placed a phone call to attorney Paul Hebert and said he had something serious to talk about. When he came that day to Hebert's office, the man was contemplating murder.

"One of his children had, the night before, been molested by the priest over in Esther-Henry, Father Gilbert Gauthe," Hebert recalled.

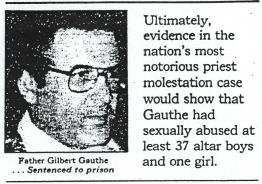

Ultimately, evidence in the nation's most notorious priest molestation case would show that Gauthe had sodomized and engaged in mutual masturbation and oral sex — in some cases as many as 200 times — with at least 37 altar boys and one girl, some as young as 7 years old.

|

Both church critics and church officials agree that the Gauthe case brought into the open the need for a change in the way the church dealt with priests who molest children — an issue that church writings show has plagued the Catholic Church for a thousand years.

But 4½ years later, U.S. Catholic dioceses and archdioceses still are struggling with the problem of priests who molest children — and sometimes are making some of the same mistakes that allowed Gauthe to escape detection for at least nine years.

Back in 1983, however, Hebert thought at first he was dealing with just three victims in a single family and one rogue priest. Gauthe had taken pictures of the boys in sex acts, coerced them into group sex acts and then threatened their lives if they talked.

"I didn't even know what the word 'pedophilia' meant," Hebert said recently.

Hebert (pronounced A-bear) was educated in Catholic schools, attended Mass regularly with his wife and three children and had acted as counsel for the Lafayette diocese on some real estate matters.

But almost as soon as he began conversations with diocesan officials, it became clear to Hebert that the problem was much deeper than one priest. From the first day, he said, the church didn't react with the shock and concern that he thought this crime would evoke in Catholic leaders — although Gauthe was removed from the diocese three days after Hebert presented his allegations.

Hebert called the Lafayette diocese in an effort to talk to Bishop Gerard Frey, but met instead with Monsignor Alex Larroque. Larroque admitted "that he had had problems of this nature — that was his word, 'problems' — with Gauthe in the past," Hebert said. "As a lawyer, it hit me in the face."

Hebert said that in the first six weeks of representing his client, his concerns were twofold: getting rid of Gauthe and seeking psychological help for the molested boys — whose numbers kept increasing. By summer's end, Hebert would represent nine boys.

As other parents in the close-knit Esther-Henry parish learned that their children had been molested, they also sought Hebert's counsel. Hebert was by then openly troubled by the church's attitude.

In a series of conversations with Monsignor Richard Mouton, Hebert said he "basically begged" for the diocese to explain to the congregation why Gauthe had left and to say publicly that it would help the victims and their families.

"The church finally said that it would put in the church bulletin that he was dismissed for 'moral indescretion,'" Hebert said.

In a meeting with Monsignor Mouton, who was put in charge of the matter for the diocese, Hebert asked that the church seek to find all of the children molested by Gauthe and that it pay for psychological counseling for them as long as they needed it.

Hebert added that if he had to file a lawsuit to get the church to perform this service, which he saw as both its moral and legal duty, he would.

"You mean a good old Catholic boy like you would consider suing the Catholic Church?" Hebert recalled Mouton as asking. "Yes," Hebert said he responded, "because it's not the Catholic Church I know."

Hebert said he asked what the Catholic Church was prepared to do and that Mouton answered, "If the kids would come in and confess their sins, and still want to go forward, we'll see what happens."

"See you in court," Hebert replied.

Hebert prepared for the lawsuit by learning about pedophilia and by sitting in on university courses about the effects of sexual assault on rape victims and minor children.

"I learned that the trauma to rape victims, which is really what these boys were, could still be felt 10 years later," he said. "I knew the case would be explosive in front of a jury, but Louisiana doesn't have punitive damages, so I had to prove how much they'd been damaged."

Hebert joined forces with Raul Bencomo, a New Orleans trial lawyer, and the two prepared a 100-page claim for settlement to present to the lawyers for the firm that insured the diocese. Insurance lawyers agreed to settle the cases without trial — paying from $450,000 to $600,000 each to the nine children victims.

Gauthe was in a Catholic psychiatric hospital by then, and the case might have escaped further notice.

But Hebert went to Lafayette District Attorney Nathan Stansbury, who interviewed 11 of the victims. Gauthe eventually pleaded guilty to molestation charges and in October 1985 was sentenced to prison for 20 years.

Trial lawyer J. Minos Simon, who'd been retained by one of the Esther-Henry families, took a new tack in pursuing the church. He went after the diocese publicly and subpoenaed the diocesan personnel files on 27 other priests he said had been accused of sexual improprieties.

Instead of complying, the church admitted liability in the case. The February 1986 trial, which received extensive publicity, essentially was held to determine the amount of damages. The jury gave the family $1.25 million, and the problem of pedophilic priests was finally out in the open.

Almost four years after Gauthe was discovered, the diocese has paid an estimated $12 million in 16 cases. About six cases are still pending against the diocese — some against another priest from the diocese.

On his way to the courthouse in February 1986, Glenn G., the father in the family that brought its suit in public, explained his motivation this way: "People have been quiet long enough."

Any original material on these pages is copyright © BishopAccountability.org 2004. Reproduce freely with attribution.